In part 2 of this series, we covered the compelling arguments for a shift away from animal agriculture. In this third article, we focus on World Two’s argument that animals are an essential component of sustainable agricultural systems.

What is Worldview Two? The answer is imprecise but could be seen as an emerging form of organic agriculture: Agroecological or Regenerative Agriculture.

The Core Tenets of Regenerative Agriculture

All farms depend on soil. Soil health is the main focus of regenerative agriculture.

“If we destroy our soil, mankind will vanish from the earth as surely as the dinosaurs” —EVE BALFOUR

Because industrial / synthetic inputs harm the fragile ecosystem of soils, this ‘soil first’ approach requires an entirely different mindset – using biology instead of chemistry. It is about farming with nature rather than against her. Monoculture is unnatural, and therefore diverse, multi-species mixed farming approaches are encouraged. Proponents, notably Gabe Brown in the US, have developed the six principles of soil health as guidelines:

1. Farm in context – Manage the land and produce food products in keeping with the local environmental setting.

2. Minimum soil disturbance. Application of synthetic chemicals and tillage (ploughing) damages soil biology and should be minimised or avoided.

3. Living root in the ground at all times – Plant growth stimulates soil biology – use appropriate cover crops, especially diverse covers, to maintain biological activity and porous soil structure.

4. Soil Armour – bare soil is degrading soil. In cases where bare soil could exist, such as between rows, it should be covered with litter, residues or mulch.

5. Diversity – use rotations, mixed / companion crops, intercropping and diverse cover crops.

6. Animal Integration – introduce animals into the rotation through cover crop grazing or silvopasture (trees) to mimic nature and stimulate biology through animal impact.

The final principle, animal integration, brings regenerative agriculture into conflict with Worldview One. It blurs the distinction between arable and animal, normally considered separate.

Introduction to Regenerative Grazing

Most commentators would probably agree that Allan Savory is the main contributor to modern regenerative thinking, as evidenced by the popularity of his 2013 TED talk, which focuses on wildlife management and ranching in Zimbabwe.

The Savory method is a holistic decision-making process that includes broad societal, financial and other factors including the needs of wildlife as well as the farm itself. But the thinking started with grazing.

Savory’s lightbulb moment was counter-intuitive and distressing. Reduced grazing pressure by culling wild populations of elephants had the inverse of the desired effect. It seemed to accelerate rather than reverse desertification. This is the logic of his findings:

- Livestock often overgraze and destroy landscapes, causing desertification (including traditional/native pastoralist systems)

- But land naturally supports large populations of ruminants / herbivores

- Removing ruminants from dry, grassy landscapes causes desertification

- There must be something different about the grazing patterns and behaviours of livestock vs wild animals affecting the relationship between animals and vegetation – not just animal numbers

- The natural relationship between ruminant and land must be symbiotic and interdependent

- Therefore – livestock should be managed to more closely mimic natural patterns of grazing behaviour

Observing nature provides clues as to how livestock can be used to maximise biological processes in pasture. The land should experience short periods of high intensity grazing, with frequent, typically daily moves to fresh ground followed by extended recovery periods. The human acts as the lion or wolf, driving the herd through the landscape. During recovery, the land is essentially left wild with the next grazing event being carefully timed with the soil and vegetation, not the animal being the focus.

The Savory team are adamant that their ranch in Zimbabwe demonstrates the success of holistic management. Including a controversial claim that we need more livestock in fragile, desertifying areas not less.

“The key to regenerating degraded land is to bring back the animals that once grazed there. ” – Allan Savory

Others from Worldview One disagree. They disagree so much that in 2018 a “corrections and updates” note was added to the TED talk. And others, including George Monbiot have directly accused Savory of untruths, pseudoscience, mumbo jumbo and even “bullsh*t”. We will save comparative arguments for future posts, so let us continue with presenting the Worldview Two case, initially in dry lands and brittle landscapes and departing from Allan Savory himself.

Las Damas Ranch

Las Damas Ranch in the Mexican Chihuahuan desert receives only around 200mm of annual rainfall during a 2-3 month rainy season. (compared to over 1500mm in the UK Cumbrian fells). You can read the case study in detail here:

- Understanding Ag case study

- Understanding Ag case study download

- PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency – Nature-based solutions and scenarios

Until 2006, the ranch was managed conventionally, with 200 cows continuously grazing 25,000 acres in three herds and 12 pastures. In common with neighbouring properties, the landscape was degrading and struggling commercially.

During a workshop teaching Savory’s Holistic methods, Alejandro Carrillo, owner of Las Damas was inspired to incrementally apply the principles he learned:

- Formed a single herd (mob)

- Increased the number of watering points

- Increased paddocks from 12 to over 500

- Cattle moves at least once per day

- Adaptive planning – move the animals according to the needs of the land

- Grazing recovery periods of around one year or more

- Selective breeding – adapting animal genetics to the environment

- Expanded the mob with donkeys and sheep

These apparently trivial measures have resulted in outcomes that are far from trivial:

- Noticeable increase in vegetation and decrease in bare ground

- Increased rainfall infiltration and water holding capacity of the soil

- No supplemental feed

- Increase in soil biology, including dung beetles

- Minimal vaccinations/medicines, especially antiparasitics

- Improved herd health

- Reduced labour

- Uplift in cow numbers from 200 to 600

- Increased revenue by 350%

Although not a validated academic study, the headline increase in stocking density – 200 to 600 heads is an impressive statistic. Impressive enough for others to seriously consider adopting the approach.

In the previous article we discussed the dichotomy between land sharing and land sparing. The idea that to save natural landscapes, humans need leave nature alone and re-wild. Las Damas seeks to be land sparing through land sharing. Humans are a natural part of natural systems, if managing using natural processes.

We will examine these claims in future posts, through the lens of output per hectare.

Temperate Climates

Moving away from the desert, to climates with year round rain, the same principles have been applied, notably Greg Judy of the USA, and James Rebanks in the UK. In contrast to Mexico, the challenge is usually around too much rain not too little. To prevent pastures from becoming muddy quagmires in the UK, cows are usually kept inside from November to March / April, even beef herds. This necessitates the cycle of haymaking on-farm, buying in feedstuffs, provision of infrastructure and management of manure.

Ambitious regenerative farmers are experimenting with keeping cows outside year-round, discovering that it is possible to mimic bison, deer, elk, or sheep, without damaging pastures. In fact, both animals and land seem to appreciate the approach. Although very different to the desert setting, the principles are similar – dense herds, short, intense competitive grazing and frequent daily moves. During the summer grazing cycle, areas are left to grow winter stockpile – effectively “standing hay” – hay without the workload. Some hay is still baled to act as a year-round buffer against shortfalls in the pasture during dry spells or snow and ice. These are rolled out onto pasture, which spreads seeds and encourages positive animal to soil impact as opposed to the muddy damage typically seen around ring style feeders.

In the lowlands of Oxfordshire, Faifarms have conducted detailed studies on outwintering. Trials over several years showed significant overall cost savings of £302 per cow (£1.68/cow/day), and a noticeable increase in wildflowers including orchids.

So far, then, we have established that there is a movement of farmers using relatively simple core principles to manage livestock in a way that mimics nature in dry lands and temperate climates. The approach can be applied to pure livestock farming or integrated into arable rotations. And it saves money.

What are the wider implications if adopted more widely?

Carbon

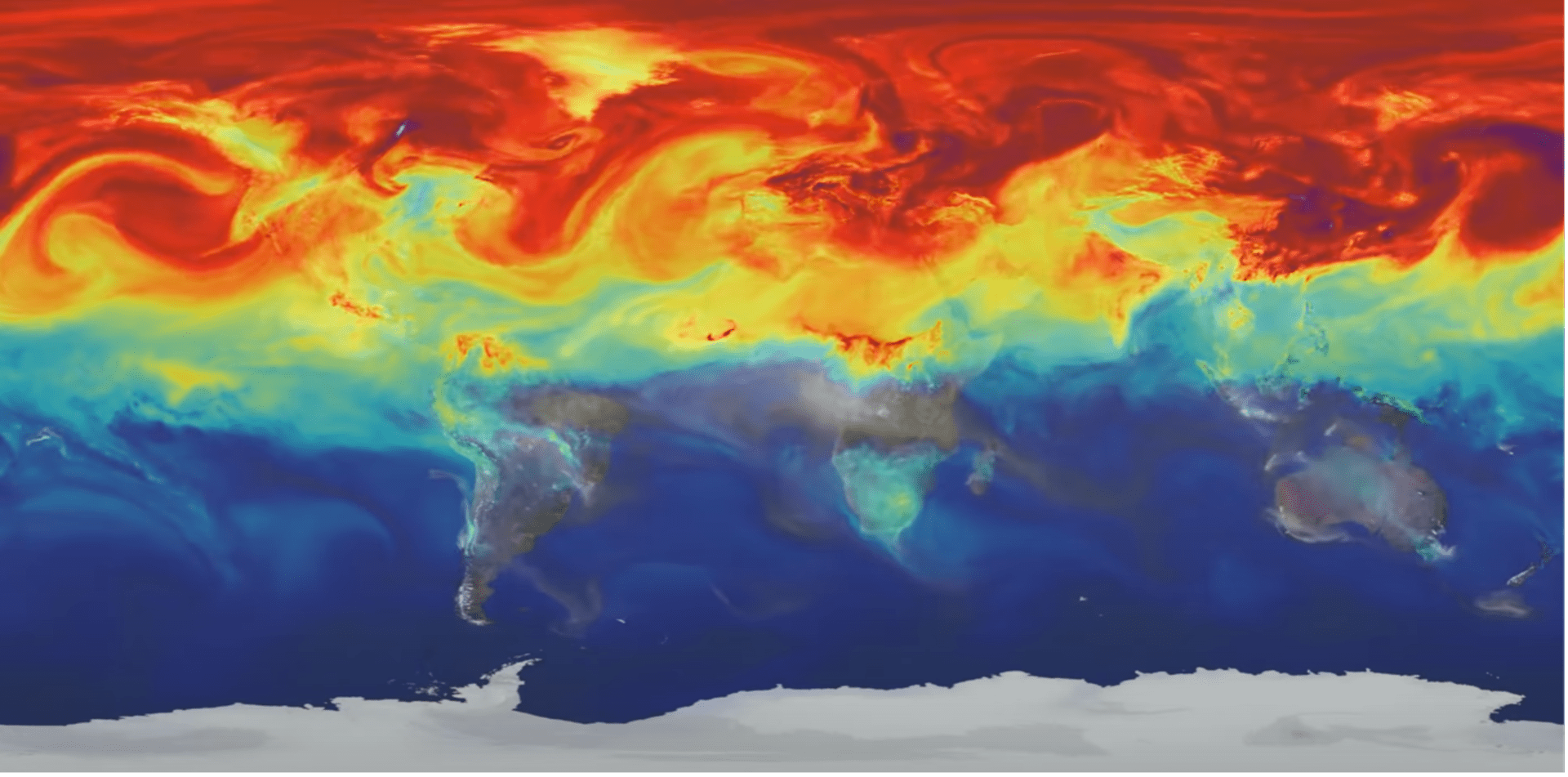

Our planet breathes. In the winter and early spring, the northern hemisphere releases CO2, but in the summer, plant photosynthesis absorbs it. You can see an animation from NASA showing this annual cycle.

This field (figure 10) is releasing carbon. You are looking at the death of billions of biological species, including fungi, bacteria, worms and other creepy crawlies. The cause of death is a combination of physical disturbance, chemical poisoning or exposure to sunlight UV. Notice also that the only active photosynthesis is in the grass boundary, the hedgerows and trees are still dormant

Figure 11, is Overbury Farm estates managed by Jake Freestone who has been developing regenerative approaches for 20 years. You are looking at cycles of life and cycling of nutrients in the soil, carbon sequestered in organic matter, animals enjoying their meals fertilising as they go, and minimal if any soil erosion. The clover even provides flowers for pollinators. This land is earning money.

In contrast, this field (Fig 12) is showing few signs of life, poor water infiltration, soil compaction and erosion. You are looking at emissions of CO2 into the air, nutrients, chemicals and sediment into the water. Nothing for pollinators. There is nothing earning money.

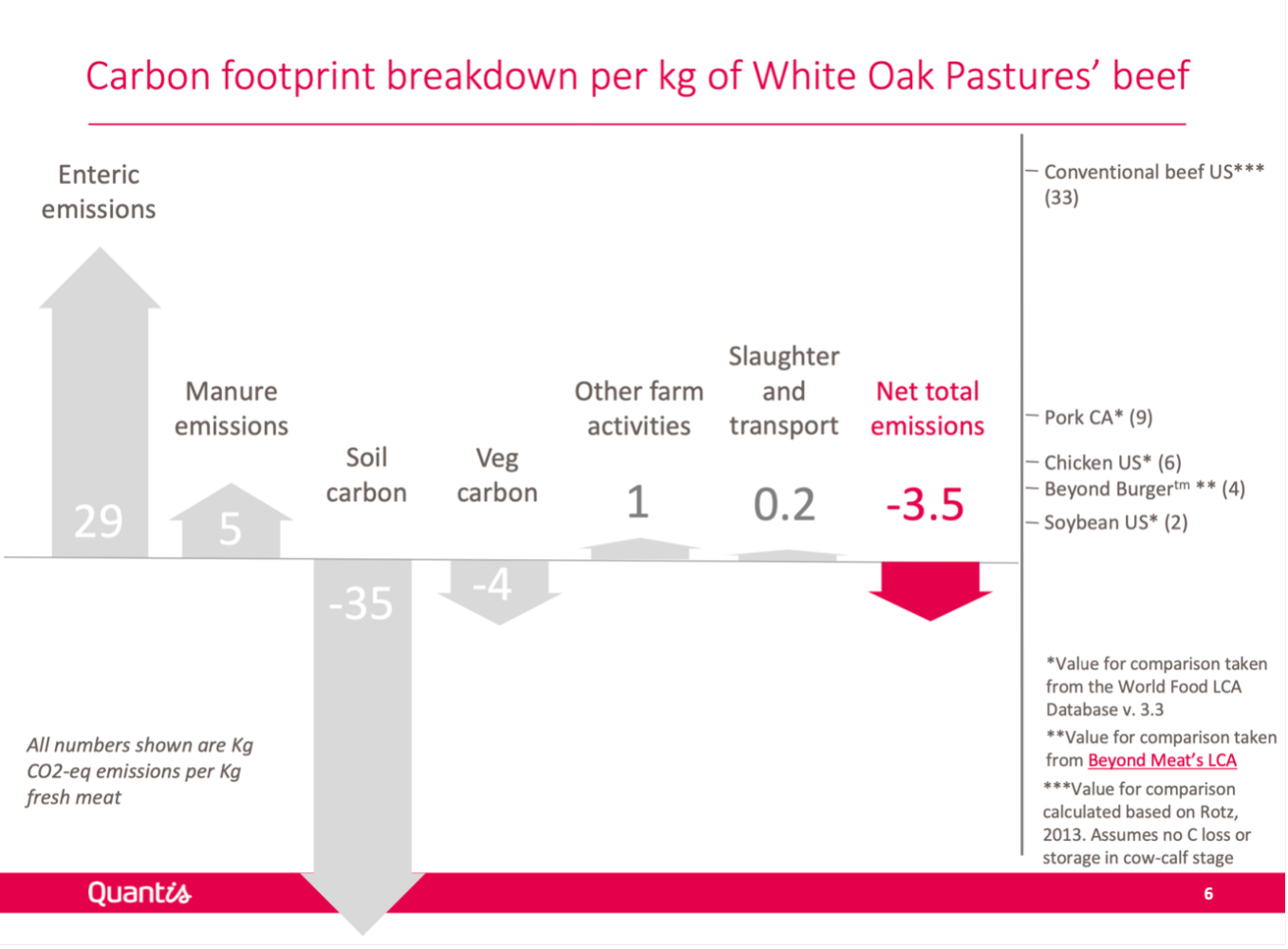

Early proponents of regenerative agriculture have argued that their methods sequester sufficient carbon in the soil to more than offset their emissions. Until recently there have been few academic studies to support these claims. However, perhaps the most significant independent study conducted to date is by Quantis, a reputable organisation that provides life cycle assessment services. Their analysis of White Oak Pastures farm in Georgia found that soil carbon sequestration more than balanced the greenhouse gas emissions of the operation with a net balance of -3.5 Kg CO2eq per kg of fresh meat.

Will Harris, owner of White Oak Pastures has increased diversity still further by adding pigs, chickens, sheep and goats into the grazing rotation, with each animal creating its own biodiversity in relationship to the soil.

But 40% of the earth surface is not like Wiltshire or Bluffton. In this semi-desert, rangeland, veld and prairie, the situation is very different. During the dry season, ungrazed grasses left alone oxidize as opposed to being incorporated into the soil through decomposition and biological breakdown. This standing dead matter, still attached to the plant inhibits regrowth in the next season. This is why large areas of grassland are managed by intentional burning. Properly managed grazing minimises the need for burning, avoiding this consequential environmental damage through emissions of CO2 and other combustion products.

Fires occur naturally in dry lands and the suggestion is not to completely eliminate this management practice, rather that such landscapes are currently over-burned and under-grazed; offering the opportunity to restore a natural balance through regenerative grazing and holistic management.

In summary, far from being a major source of carbon emissions, when managed well, it is claimed that livestock can be the tools necessary to create a net sink. More research is emerging that supports these claims and a vault of papers is curated here.

But, what about Methane? Worldview One claims that just the emissions of methane are sufficient justification to severely restrict livestock farming.

Methane

Methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and the comedic aspect of being able to talk about cows belching and farting methane perhaps leads to the ubiquitous connection between diet and climate. It is fun to talk about, and leads to the simple notion that eating less meat will help solve climate change.

This makes sense based on World One assumptions; leading to headlines such as:

“Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production” from the Guardian.

But there is much more to methane than meets the eye. There are three main points to consider; Significance, Sources and Sinks.

The significance of methane to date has been calculated using the Global Warming Potential – GWP100 framework. This attributes the warming potential of a methane emission event based on its warming potential as it decays to almost nothing over a 100 year period. An alternative metric, GWP* has been proposed by researchers at University of Oxford which takes into account methane’s flux balance. Like having a tap in a wash basin running with an open plug hole, the water level only rises when you increase the flow. It has been calculated that methane’s effect on global temperatures using GWP100 “has been over-estimated by a factor of three to four“. Therefore, assuming the “plug hole” stays the same size and methane is broken down at a constant rate,(which we will return to later) the warming effect from livestock originated methane only increases in line with increasing livestock numbers. This raises the question “what were the ancient historic natural enteric emissions from ruminants?” How many grazing animals roamed the great plains of north America, Siberia or Africa? Worldview One suggests numbers of livestock now vastly outnumber and outweigh historical natural stocks by four to five times. However, this Nature article suggests that the difference may actually be minimal, including a statement “it becomes clear that previous interpretations should be handled with extreme care”. The Worldview Two argument is that if livestock interact with landscapes in a natural manner, then they cannot be a problem.

The debate continues on this topic…..

That methane levels have increased from around 725 ppb in 1750 to nearly 2000 ppb today is not contested. It is a big concern. This means understanding the relative proportions of methane sources is crucial. There are a myriad of natural sources of methane; phytoplankton, algae, molluscs, saprotrophic fungi, cockroaches, termites, arthropods, volcanoes, forest fires, soil degradation, wetlands, peat bogs, glacial melt water, permafrost melt, rivers, lakes, even beaver ponds and human digestive systems. Recent satellite launches (GHGSat , Sentinal5P) have enabled us for the first time to accurately and with high-resolution show emissions in near real-time. By detecting radioactive isotope markers, it is even possible to trace the emission source category. Although there is still uncertainty in the accuracy of these assessments.

In 2017, the BBC ran a story about a study on Baltic sea clams. The study’s co-author Dr Ernest Chi Fru, from Cardiff University’s School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, said: “globally, apparently harmless bivalve animals at the bottom of the world’s oceans may in fact be contributing ridiculous amounts of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere that is unaccounted for”.

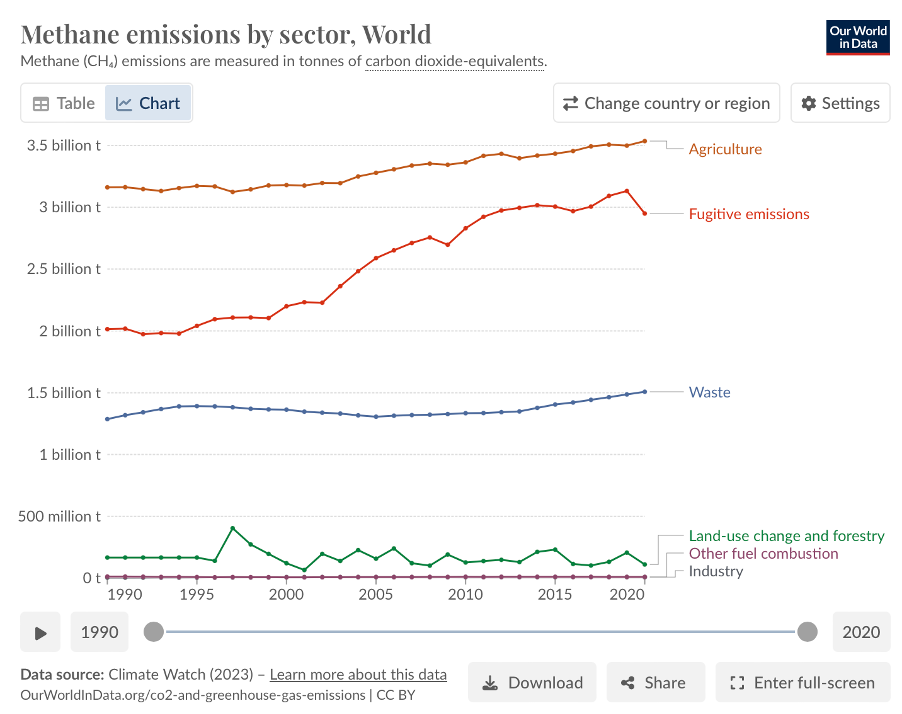

Despite the uncertainty, the overall trends from sources such as Our World in Data show that fugitive emissions from oil, gas and mining are the primary source of increased emissions.

Although many of the reports from surveillance activities include photo’s of cows, the case studies of worrisome large scale methane emissions are from industrial sources – fugitive emissions. And those fugitive emissions of deep sources of methane from activities such as poorly controlled fracking have no balancing process associated with production. But grazing livestock, managed regeneratively do have a balancing process. And some suggest that the balance tips very heavily in favour of the sinks side of the equation. Walter Jehne is quoted as suggesting that in dry lands, a ruminant can stimulate 100 times more methane breakdown than it emits. A claim significantly at odds with the conventional narative. How so?

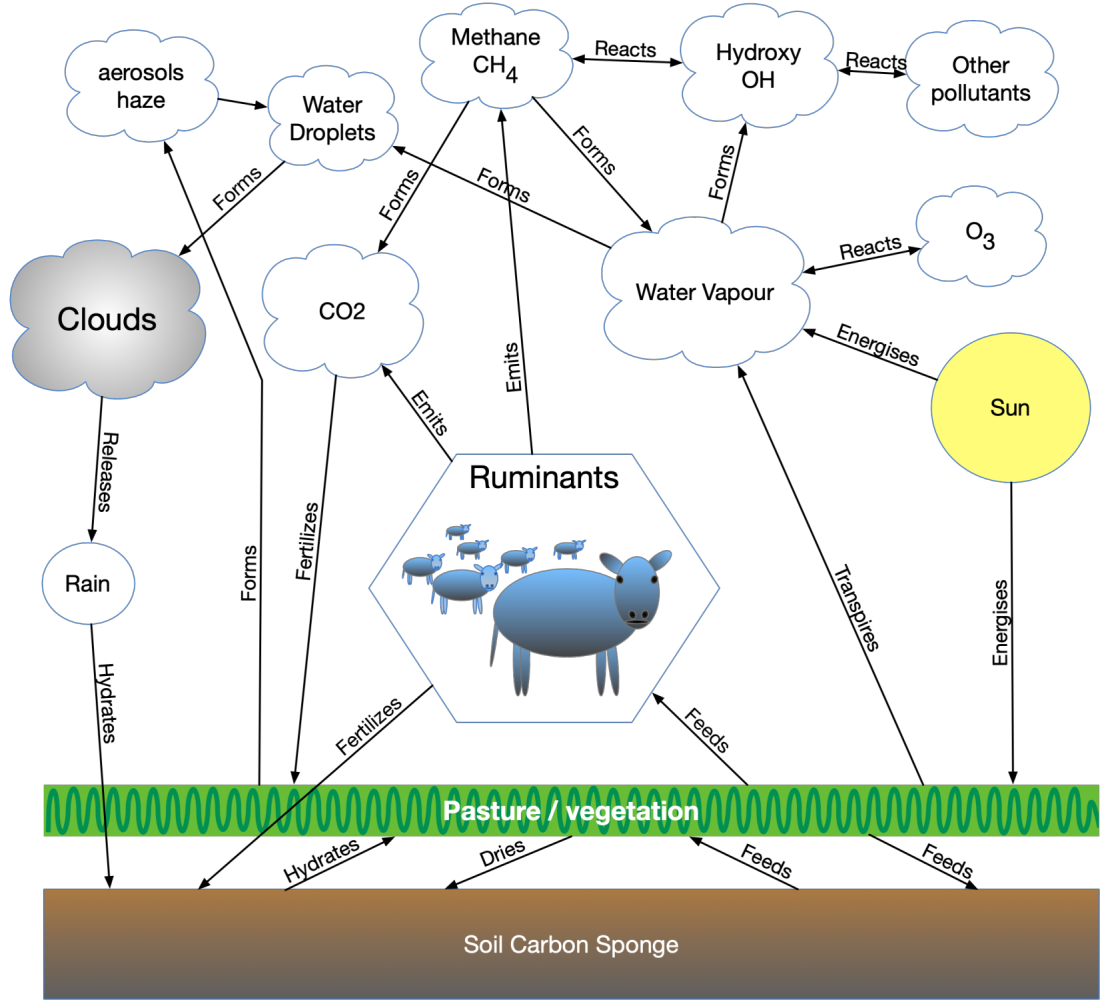

Methane is broken down in the atmosphere though reaction with hydroxyl radicals (OH) formed by the photo oxidation of water vapour together with ozone. This is a fast and very efficient methane scavenging reaction, but high reactivity means that the OH molecules only exist momentarily before reacting with something, not just methane. This atmospheric “cleaning” function therefore requires OH to be constantly formed and replenished.

Impairing the atmosphere’s capacity to scavenge methane is equivalent to blocking the plug hole. Desertification inhibits the transpiration of water vapour, which is crucial for the formation of OH. Fine dust particles, pollutants and other reactive compounds also use up stocks of OH, leaving methane unprocessed. Properly managed livestock as per Las Damas, increase transpiration which increases OH production as well as aerosol haze which creates clouds and in some circumstances rain. This virtuous cycle is thought to lead to net reduction in methane – as well as the scavanging of other pollutants.

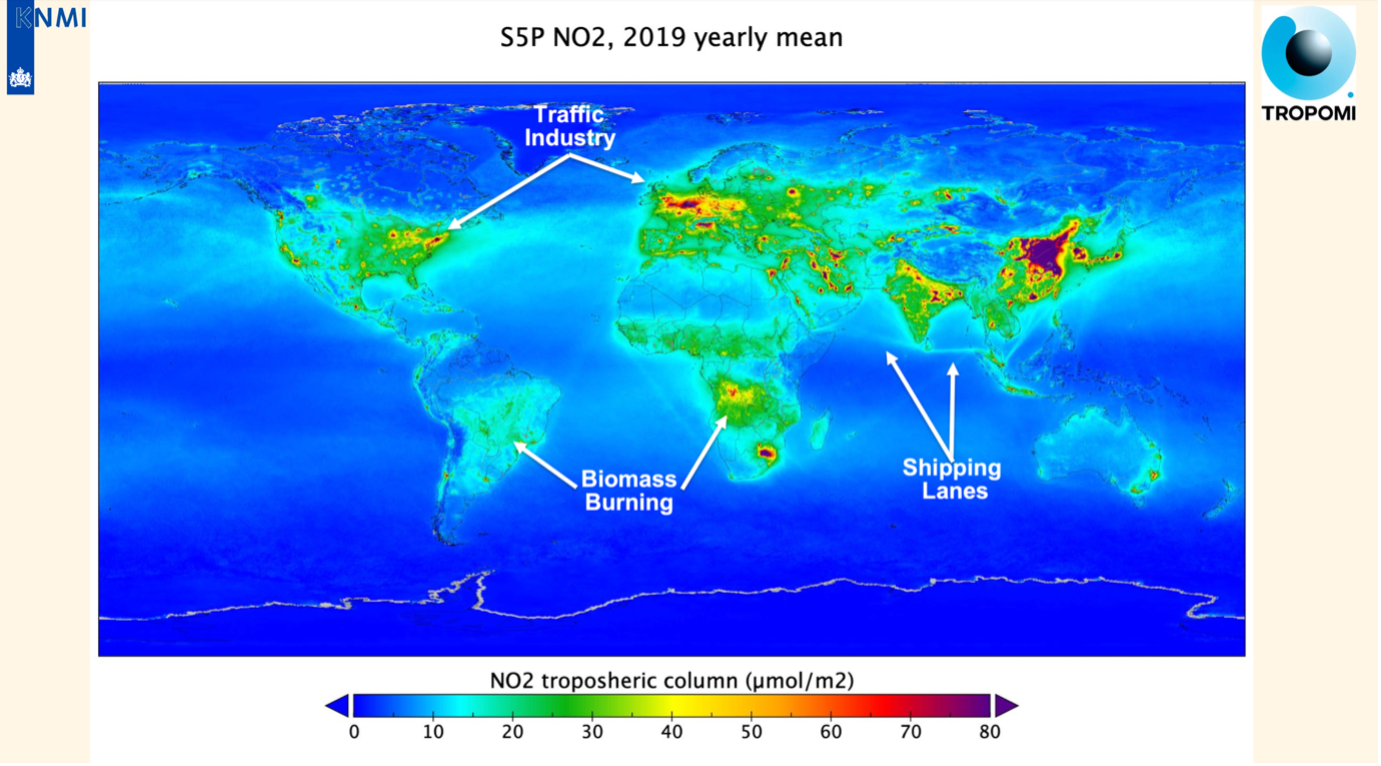

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is a good marker of combustion pollution, and you can see from Fig 17 that there are significant hot spots relating to population and industrial centres, but also significant contributions from biomass burning which use up OH that would otherwise scavange methane.

To summarise the methane topic. Properly managed grazing in dry lands directly reduces methane emissions (and other greenhouse gasses) by reducing the need for biomass burning. It supports the production of atmospheric hydroxyl free radicals that scavenge methane. Both of these effects are enabled by the formation of a healthy “soil carbon sponge”, which holds moisture, extends plant growth duration, sequesters carbon and increases atmospheric water vapour through transpiration.

Which nicely brings us to water.

Water

The ability of soils to infiltrate and retain rainfall is crucial to the health and productivity of a landscape. Without organic matter, soil is sandy dusty dirt. Gabe Brown reports that in the early 1990’s following conventional farming practices, the silt loam soil on his ranch could infiltrate just half an inch of rain per hour and was at 1.7-1.9% Soil Organic matter (SOM). By 2011, with SOM over 5% it could infiltrate upwards of 8 inches per hour, and by 2021 over 30 inches. Combined with cover crops, this eliminates soil erosion and nutrient runoff. This change hydrates the landscape, recharging aquafers that act as a source for boreholes. In this context, it can be argued that livestock are a net producer of water in contrast to the Worldview One argument that livestock farming is only ever a significant drain on water resources.

The rule of thumb guideline is that each 1% increase in SOM stores an additional 27,000 Gallons per acre (252,500 litres per hectare). The soil carbon sponge again. If true, one can see how regenerative grazing management can easily encourage water-holding capacity per hectare far in excess of the thirst of a single beast, especially in arid land. Gabe Brown is often quoted as saying “it is not how much rain you get, is how much you keep”

Back in the UK, water companies such as Severn Trent Water have introduced schemes to encourage farmers to introduce regenerative practices. They aim to minimise pollution from nutrient run-off in areas sensitive to water quality issues.

In upland settings, regenerative management of pastures increases soil water holding capacity and standing vegetation, reduces runoff and slows water down reducing flooding risk downstream, recharges aquifers and builds drought resistance. Limiting sediment runoff also reduces the need for dredging silted waterways, whilst restricting eutrification from algal blooms initiated by excessive nutrients.

Animal Welfare / Ethics

There is agreement that conventional intensive farming of livestock is sometimes cruel and unacceptable, with excessively dense confinement.

But animals can be integrated within food systems whilst enabling them to express natural behaviours and instincts. Long rest periods between grazing events breaks parasite reproductive cycles, often eliminating the need for anti-parasitic treatments. Calves are often kept at heel and weaned naturally. Organisations such as Pasture for Life emphasise such practices in their certification standards. Chickens are kept in moving pens to follow the grazing sequence and pigs are allowed similar freedom.

Of course the end result for most farmed animals is slaughter and the plate. If the ethical position is that intentionally ending a life is not justified under any circumstances, then there is no arguing with this. However, if we consider the case of Las Damas, a single cow is deemed to be responsible for supporting and regenerating several hectares of land, providing habitat for a myriad of creatures that would otherwise not exist. Therefore, the purposeful life and humane slaughter of a single animal is ethically justified by the existence given to many other creatures as part of the natural circle of life.

Human Health

The foods we eat today are very different in nutrient profile to those of even 50 years ago. And not in a good way. Chemical crop protection and fertilisation systems that increase bulk productivity, harm the complex biological interactions between plants, bacteria, fungi and other beneficial organisms, including nematodes and worms. This inhibits plants from taking up inorganic micronutrients such as magnesium, calcium, selenium, zinc, iron, and copper. The recent book What Your Food Ate (Montgomery and Biklé) delves into the detail, comparing foods grown in neighbouring farms but with contrasting management practices. Produce from regenerative farms was found to be substantially more nutrient dense than farms using conventional management.

Metrics used by farms, buyers and governments are typically based on the weight or calories of the crop per unit area of land. However, the overriding function of the land is to support human health through nutrition, which is dependant on minerals and micronutrients as well as calories. These are difficult to measure, meaning consumers are unable to make a fully informed value decision on the quality of the food that they are buying. There are initiatives such as the Land to Market mark, which is an ecological outcome verification system where consumers can be sure that food with that label is from regenerating land. This implies that it is not just good for the planet but for good for the consumer.

The extreme dietary position of Worldview One is vegan – all plants no animals. The equivalent Worldview Two position is carnivore; all animals no plants. The most extreme version is to eat only beef, known as the lion diet. This may appear to be a fad diet, completely at odds with mainstream dietary advice and with potentially severe negative health consequences. Rising popularity on social media has drawn the attention of researchers, including this 2021 paper by Lennerz et al on self reported health status of 2029 carnivore diet consumers. This does confirm reports of health benefits, but the nature of the study clearly serves to highlight the need for more research.

A less extreme perspective is that as part of a balanced omnivorous diet, animal based components provide humans with high nutrient density and bioavailability. Increasing children’s access to animal based foods in developing nations especially is essential to health, well-being and development of the rising generations in the global south especially.

Worldview Two in a Nutshell

Animals are an essential component of a healthy agricultural ecosystem. By managing livestock in ways that mimic natural processes, the damage done by decades of intensive food production can be reversed, and land regenerated.

In doing so, dry landscapes can be rehydrated, carbon sequestered, methane scrubbed, biodiversity enhanced and human health supported through improved nutrition. And all this achievable without compromising economic viability.

It is not the cow, it’s the how.

Much of what we have described here is 180 degree polar opposite to Worldview One. As policy makers, consumers, voters, retailers, farmers and activists, what are we to think? Is one view right and one view wrong. Are there elements of agreement? Where do you sit in this?

There are several documentaries which dig into the topic including:

Sacred Cow (2020) – free to watch on YouTube

Kiss The Ground (2020) – on Netflix

Six Inches of Soil (2024) – being rolled out this year

Good luck finding your own way through the conundrum.